Research Project Overcomes Traditional Barriers to Screening and Prevention

by Chisholm Pothier

Growing up in an Ojibwe speaking home with little access to health resources or education, Theresa Morrisseau hadn't thought much about cancer prevention in her life. But a TBRRI-LU research project has made her an advocate for screening and testing.

Growing up in an Ojibwe speaking home with little access to health resources or education, Theresa Morrisseau hadn't thought much about cancer prevention in her life. But a TBRRI-LU research project has made her an advocate for screening and testing.Theresa Morrisseau hadn’t really thought much about cancer in the first 59 years of her life.

“I’m a very stubborn person,” the now 60-year-old Elder of Rocky Bay First Nation, says matter of factly. “I don’t go to the doctor because I have a sore leg. There’s got to be something seriously wrong with me, the leg is falling off, before I go see a doctor.”

But she has a daughter-in-law who might be just as stubborn. Kyla Morrisseau is involved with the Anishinaabek Cervical Cancer Screening Study (ACCSS) as a research assistant in her own community and bugged her mother in law to join in until she finally relented. What she learned about the incidence of cervical cancer among Indigenous women and the importance of screening was a revelation.

Cervical cancer is highly preventable using Pap screening and testing for Human papillomavirus (HPV), the main risk for cervical cancer.

Despite these options, according to the ACCSS web site, First Nations women endure notably higher rates of diagnosis and mortality due to cervical cancer. First Nations women are less likely to seek out medical care until it’s absolutely necessary. They have less access to education on health issues, and have to travel significant distances off reserve to get even limited access to health care.

Addressing factors like remote geography, transportation issues and lack of adequate health resources on reserves, as well as cultural barriers is the goal of the ACCSS.

The ACCSS project is based in Thunder Bay and involves 10 First Nations communities in Northwestern Ontario. It is premised on the safe assumption that if cervical cancer screening and follow-up of abnormal results is better organized in First Nations communities, the incidence of cervical cancer will go down. Dr. Ingeborg Zehbe set out to find innovative educational tools to promote the screening that would see greater participation.

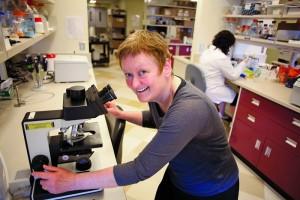

Dr. Ingeborg Zehbe's research project was looking for innovative ways to provide cancer screening and prevention education that would be effective in addressing the higher rate of cervical cancer among indigenous women in Canada.

Dr. Ingeborg Zehbe's research project was looking for innovative ways to provide cancer screening and prevention education that would be effective in addressing the higher rate of cervical cancer among indigenous women in Canada.

Dr. Zehbe is a researcher at the Thunder Bay Regional Research Institute (TBRRI) leading the ACCSS. She consulted Dr. Pauline Sameshima, the Canada Research Chair in Arts Integrated Studies at Lakehead University, about how to get the message of the importance of screening across to Indigenous women effectively. Dr. Sameshima found a way to integrate art into the education part of the project in an attempt to increase dialogue and communication. In a pilot, participants metaphorically took charge of their own wellbeing by creating their own design through felting Styrofoam balls representing HPV.

What ensued was almost magical. The line between the researchers and community members disappeared as each worked on their ball, chatting as they did.

“The difference in the amount of back and forth dialogue between the time people were felting and the time we didn’t use felting, was phenomenal,” said Dr. Sameshima. “At the end of the felting, when all the balls were out, there was a real sense of community.”

The study can say it has saved at least one life. Armed with the information she received at the felting session, Ms. Morrisseau sought medical attention when she had a persistent sore rib.

Testing discovered she had cancer and it was causing her bones to break. Her treatment was successful. Ms. Morrisseau isn’t sure she’d be alive today if she hadn’t acted when she did.

In the aftermath of the felting session, some of the other women participating who had not previously been screened went and got screened. And a roomful of women are now talking about their experience with their friends and neighbours.

“The ladies go home, like I do, and talk about it,” Ms. Morrisseau said. “They have a cup of tea, like I did with my sister and tell her what I went through. Actually my sister’s done a couple of tests because of what I went through.”

That cascading effect in the wake of the workshop is an important part of the project, says Dr. Zehbe.

For more information on the Anishinaabek Cervical Cancer Screening Study visit its web site at accssfn.com